Transplanted Taxonomy – Notes on Art, Language, and Nature

I found myself immersed in Peter Nadin’s work shortly after seeing First Mark, his solo exhibition at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in Summer 2011. I was impressed by Nadin’s ability to seamlessly merge his artistic process with his farming practice, using raw materials from his surroundings to create works that were the direct product of the farm and its landscape.

The First Mark paintings and sculptures were of the earth but moved beyond what we would call land art or earthworks. His are not marks made on the land, but marks that emanate from the land – they exist as both a product and a representation of the farm. Cashmere, honey, wax, eggs, ham, black walnut, and charcoal – all products of the farm – frequently turn up as materials in his art. In a true collaborative spirit, Nadin even coats some of his linen canvas with honey and wax, inviting bees to work the surface of the paintings as they retrieve some of what he had stolen from their hive.

My impression of the farm was enhanced by a selection of film clips featured on Nadin’s website. I was attracted by the simplicity of their content: squash blossoms, the thinning of carrots, swarms of bees, and pigs meeting other pigs. These images in grainy super 8 and 16mm seemed to be found documents from a farm long ago, and I was drawn to their rawness and the lack of an obvious statement or commentary. Even without the artist’s hand or influence, so much of gardening and farming is creative: the tools, the labor, the working of the land, and the design and layout of a garden; even the snorting and squealing of the pigs, and the way the goats run about. It’s theater with the farm as the stage.

Nadin is reluctant to call farming art, but he understands how each influences the other and that the impulses guiding both practices can be equally creative. He explains, “A carrot is not a work of art. I'm not proposing that anyone think of a carrot as a work of art. But what I am saying is that a carrot and the art I make here are both results of the same process.”[i]

Cattails along the edge of a pond on Old Field Farm. (Photo: Chris Murtha)

As the Curator of Exhibitions at The Horticultural Society of New York (The Hort), this approach instantly struck a chord with me. The Hort is a non-profit organization that has been promoting and advancing the vital connection between people and plants for over 110 years. Our cultural programs, in tandem with our social service and educational initiatives, educate and inspire a broad community of New Yorkers, many of whom have never had access to farm fresh produce, green spaces or art. Our Gallery presents exhibitions that highlight the creative intersection between art and nature, showcasing emerging and established contemporary artists who are inspired by botany, landscape, horticulture, and the environment.

On one visit to the Hort, Nadin was pleased to see that our annual exhibition of contemporary botanical art was on view in the gallery. He immediately brought up the subject of taxonomy.

Botanical illustrations were fundamental to the development and dissemination of plant science, as well as the growth in popularity of gardening. They provided a precise visual representation of plants to aid in identification and use, in addition to conveying the beauty of the plant world. Similarly, plant classification or taxonomy, established in the 18th Century by Carolus Linnaeus, introduced a fixed categorical system in Latin for plant identification to overcome the idiosyncrasies of common plant names.

Taxonomy, it turns out, had become an important element in the project Nadin was currently working on for the Hort’s gallery. As a poet, Nadin was probably attracted to the intricacies of the language in the Linnaean system, but I suspect he was also intrigued by its inherent limitations. After all, the Linnaen system, which is still in use today, is entirely in Latin, a dead language. In return for universal, static precision, what is lost? While common plant names are unstable and changing, they usually offer a broader context for the plant – a connection to history and cultural usage.

Botanical illustration presents a similar question. While these illustrations offer stunning visual realism and detail, the specimen is often depicted floating in space. The plant is disconnected from the context of its environment – the landscape, soil, and worms – and divorced from those who encounter it – humans, animals, insects, etc.

Nadin’s work does not oppose science – in fact, he teaches a course at Cooper Union on the relationship between cognitive science and art. Rather, he is searching for something more elusive, a deeper sense of the conscious in art. Before he became a farmer – and before the revelations of his First Mark series – his attempts to achieve this heightened consciousness involved working through several genres and modes of representation. In an interview with Nick Lawson in 1992, Nadin says, “I wanted to find out where the truth lay for me, within abstraction, representation, portraiture, and assemblage.”[ii]

Still Life and Window (1988) typifies Nadin’s exploration during this time. Here, he shows us three different images of a pear: One is a representational painting of a pear (presumably a found object) that is framed and hung on the surface of the painting; another is a photograph of a pear; and the third is an abstract gesture resembling a pear. Nadin’s more recent work takes this exploration one step further in an attempt to identify the consciousness of the pear, how the pear might define itself.

In order to even approach this dilemma, Nadin determined that he needed to “unlearn” how to make art. In his own notes on the First Mark series he explains, “What I wanted to do was not only represent the feeling of consciousness but also embody it. To do that, I had to leave behind the methods of representation. I knew I had to unlearn what I knew about making art—not forgetting it so much as losing my self-consciousness of it. […] The language I was using felt too restrictive for the experience I was trying to describe. I couldn’t go further without radically refining my use of the language of paint.”[iii]

Nadin is careful to distinguish between forgetting (skills or training) and losing one’s self-consciousness (inhibitions and cultural norms). More than untraining his hand, he needed to loosen his gesture (or mark) and open up his mind. The language of paint is not just forms, brushstrokes and images, but also what we accept as appropriate for our time, or appropriate as art. It is somewhat unusual to see such frank abstraction in a Chelsea gallery these days, but Richard Milazzo explains it well in his essay for the First Mark catalog: “It is not the paintings that are abstract, but our experience—of nature and the world and life—that has become abstract.”[iv]

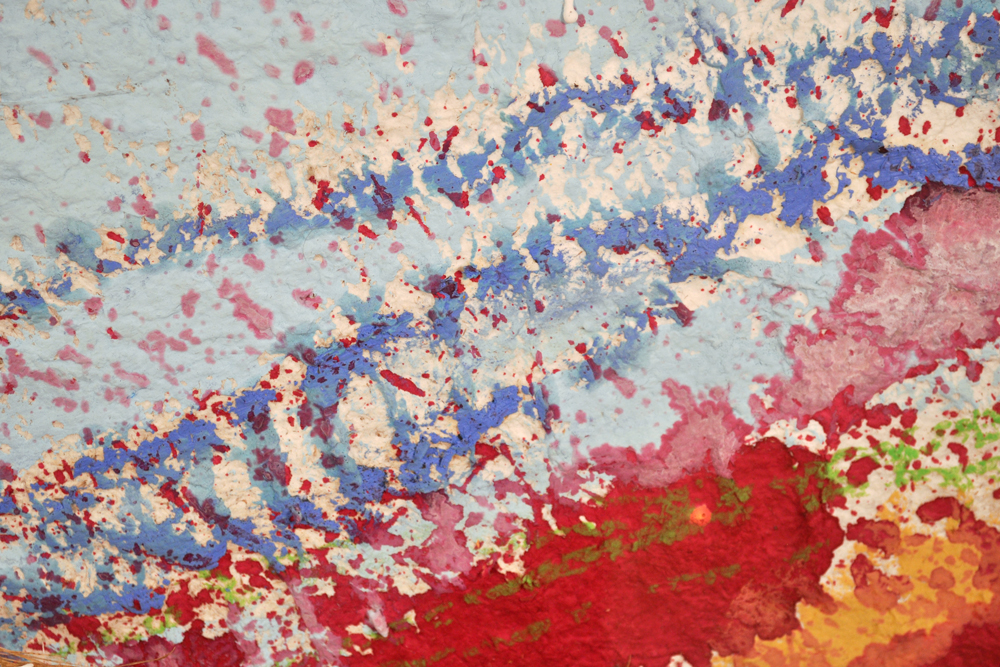

Detail of Peter Nadin, Wheat III, 2012, Triticum, pigment, handmade bamboo and cattail paper, 64 x 40 inches. (Photo: Chris Murtha)

In most figurative or representational forms of art – and often even in abstraction – the hand is subservient to the object being drawn. This is something that struck Nadin when viewing the botanical art on display at The Hort. He was amazed that the hand can be so faithful to its subject, but I also sensed that it seemed like something terrible to him. Like a trap, perhaps, or a surrendering. It almost seems as if the tables have been turned, that the artist has been commissioned by the plant to paint its portrait. The process of unlearning that Nadin was exploring was designed to find a deeper symbiosis between artist and subject, to return the artist’s hand to a gesture that is free enough to bridge the gap.

The marks that make up his recent paintings are the result of this unlearning. Nadin explains, “The language I had used was exhausted. Instead, I found great beauty in the unintentional marks left by the processes of the farm, that is, the marks on the side of the beehive made by working in the hive. I attempted to use and codify those marks into art. […] I realized that the first marks used in art-making were the universal ones made from the movement of hand and body and that they had to be common to all human cultures. In effect, they constituted the originating DNA of art.”[v] For Nadin the first mark is the one made without the constraint of self-consciousness. It is an attempt at locating that pure consciousness.

Nadin practices unlearning language as well. In his poetry, he tests the flexibility of language, even creating a new language, or at least expanding the one at hand. In a section of “The First Mark,” language becomes very malleable – punctuation eases up and words stutter, break apart and run into each other:

Put the mark on the page and spread it out

Tbeornotseebeingandconventionseebesee

Sacred (sacred) defiled by a smirk and happy

Crap.

Ah yes, our cultural theory a story is in

Ev inin ev in ev inev it table explains

The sun shine and the shoe shine the rain falls,

And the fastball. [vi]

The process of unlearning, whether in his art or poetry, has allowed Nadin to explore or (maybe more accurately) discover forms that his conscious mind might not have allowed to surface.

Nadin insists that the works in the First Mark series “continue what my work has always been about, which is giving form to experience. Where these have progressed is that now they represent consciousness itself, a form of pure consciousness that moves beyond the conscious self as represented in memories, thoughts, ideas, etc.”[vii]

Nadin strives to go beyond even those common modes of consciousness to a pure consciousness, which is something that we may not even recognize, as it may not relate to what we conceive to be our lived human lives. It is a consciousness before memory, in the sense that the tree knows to make sap, to drop its leaves, and go to seed every year. Nadin is attempting to approach what it is to be purely human.

Farming has played a crucial role in Nadin’s quest to find this primordial consciousness – the notion of being before memory and even experience. The farm enabled him to return to the land, to commune with the animals, to relinquish himself and his consciousness to the cycles of the plants, the bees, the pigs, all of which together create the cycle of the farm. And all of this in the hopes that it would inspire his own consciousness to surface and merge with that of the farm.

In the works that he has developed on the farm, this method of letting go enabled him to more directly interact with the creatures and the landscape of the farm. The pigs, bees, soil and trees all become integral to the process and their respective consciousness or being becomes part of the collective consciousness of the work. In the end, the farm – its landscape and inhabitants – are no longer subjects of Nadin’s work. They have become active participants and collaborators.

Coda

Over the last few months, Nadin has been producing handmade paper on the farm for the work that will be featured in his exhibition at the Hort. The paper is made from cattails that grow in the bee pasture adjacent to his barn-like studio. The plant and its fibers are ground into a pulp inside the studio and then taken down to the pond. Nadin gets in the pond up to his waist with a screen large enough to make 6-foot sheets of paper. He explains to me, “the pond is always level…and still, so it’s perfect.” And I’m impressed that he’s found yet another way to incorporate the farm and its landscape into his process. After he has sifted the paper and squeezed out the excess water, the screens are leaned up against the south-facing wall of his studio, and left to dry in the sun. Excitedly, he tells me that paper is quite simple—“it’s just cattails, water, and sun.”

In his film, The First Mark, Nadin says (in a voiceover, as we cut from an image of the artist squinting in the sun to one of sliced beets on a roasting pan), “The representation of consciousness, most of the time, resides in form.” He goes on to ask a question that is central to his thought process: “But what about the gesture that makes the mark?”[viii] In his recent works, this gesture can be that of Nadin as a farmer thinning a carrot, but it can also be the bee, doing what bees do, protecting the hive as it works one of his paintings, making a mark that to us resembles painting but to the bee, it’s just doing what it does. The gesture can also be the countless cattails, whose very form is gestural, that leave their impression in the paper, to be immortalized as a work of art.

This essay was published as the introduction to Peter Nadin: Taxonomy Transplanted, Art, Language, Farming, which was published by Edgewise Press in conjunction with the exhibition Taxonomy Transplanted at The Horticultural Society of New York, December 12, 2012 – February 8, 2013.

Notes

[i] Randy Kennedy, “Among the Piglets,” The New York Times Magazine, July 3, 2011, page MM28. Title of online version: “Farm to Gallery: Peter Nadin’s Comeback.”

[ii] Nick Lawson, “Interview with Peter Nadin,” in Peter Nadin: Recent Work and Notes on Six Series (New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 1992), p. 35.

[iii] Richard Milazzo, “Peter Nadin: An Odyssey of the Mark in Painting,” in Peter Nadin: First Mark (Milan: Edizioni Charta, 2007), p. 31.

[iv] Ibid, p. 32.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Peter Nadin, The First Mark: Unlearning How to Make Art (New York-Paris-Turin: Edgewise Press, Inc., 2006, p. 48.

[vii] Milazzo, p. 42.

[viii] The First Mark, film by Natsuko Uchino and Aimée Toledano, written by Peter Nadin, 7 min., 2007, Super 8 and 16 mm film transferred to DVD.